Threads of Rebellion in Widow's Peak

- michellebennington

- Nov 10, 2025

- 6 min read

Widow's Peak , the last book in the Widows & Shadows series, takes place in 1803 in the height of the industrial revolution. The industrial revolution began around 1760 when inventions, science, and technology began making great strides to make our lives easier and more comfortable. However, as a result, those in the working classes were the most deeply affected as they lost jobs to advancing technology. As they lost work, they often lost homelands too as they migrated from countrysides to cities or from one nation to another in search of work. As the industrial revolution intensified, so did the tension between the working class and the upper class--a tension that continues to this day.

This was a sensitive point I wanted to highlight in Widow's Peak in order to give depth and a sense of realism to the novel. However, one sticking point: there weren't any rebellions in Edinburgh in 1803!

So, as any author with a deadline would do, I took some artistic license and found a rebellion that would fit my purpose and shifted it through time and place (I do explain this in the Author's Note in the book too!)

Enter the Calton Weavers.

The story of the Calton weavers is one of grit and resilience. These skilled handweavers formed a tight-knit community in the village of Calton, just outside Glasgow, Scotland, during the 18th century. Though now absorbed into the city, Calton was once its own little world—an independent village with its own rules, rhythms, and reputation. And at the heart of it all were the weavers, working their looms in homes and workshops, producing fine linen and cotton cloth that made its way across the globe.

It all started in 1705 when Walkinshaw of Barrowfield bought pastureland from Glasgow, then known as Blackfauld, and began building a weaving village.

His involvement in the 1715 Jacobite rising didn’t end well, and the land was eventually reacquired by Glasgow Town Council in 1723. They renamed it Calton, and by 1730, it was sold to the Orr family. Despite being so close to Glasgow, Calton remained independent until 1846, and that autonomy gave its weavers a bit of breathing room—especially when it came to dodging the influence of the powerful Glasgow weavers’ guild.

But even independence came with strings attached. In 1725, the weavers of Calton and neighboring Blackfaulds struck a deal with the Glasgow guild to regulate the industry and avoid cutthroat competition. That deal came with a price tag—literally. As late as 1830, Calton weavers were still paying dues to their Glasgow counterparts, including five groats per loom and thirty pounds Scots annually.

Throughout the 18th century, weaving technology steadily improved. The fly-shuttle, introduced around 1780, was a game-changer, doubling productivity and making cloth more uniform.

Demand was strong, especially from Britain’s colonies in North America and the Caribbean, where linen was a staple. At the height of Calton’s prosperity, weavers could earn up to £100 a year—a solid income that elevated them socially and gave them a voice in civic life.

The weavers weren’t just craftsmen; they were thinkers and organizers. Calton was known for its clubs and friendly societies, which ranged from educational book clubs to wage-focused labor groups. These early associations laid the groundwork for what would eventually become trade unions. And while Glasgow struggled with sanitation and governance, Calton was surprisingly well-run. Lodging houses were licensed, sanitary regulations enforced, and the streets were kept clean thanks to a network of well-maintained sewers.

But the good times didn’t last. The Industrial Revolution brought sweeping changes, and not all of them were welcome. Between 1760 and 1830, the Lowland Clearances (I'll write about that later) pushed rural families into cities, flooding the labor market and driving down wages. Many of these displaced workers had few skills beyond weaving, and they crowded into mills, competing for jobs.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 added returning soldiers to the mix, and Irish immigrants further swelled the population. By 1851, nearly a quarter of Glasgow’s residents were of Irish origin. Though often scapegoated for crime and unemployment, records show the Irish were actually more willing to work and less likely to seek public assistance than their Scottish neighbors.

Mechanization hit the weaving industry hard. The flying shuttle, steam-powered spinning mills, and power looms revolutionized production but left handweavers scrambling to keep up. The first steam-powered mills appeared in 1798, and by 1810, power looms were already being used in Scottish linen weaving.

These innovations made cloth cheaper and faster to produce—but they also made many weavers obsolete.

In the summer of 1787, tensions boiled over. Calton’s journeymen weavers demanded higher wages, and when their demands weren’t met, they took to the streets. Strikers cut webs from the looms of those who kept working and burned warehouse goods in bonfires. On September 3, city magistrates tried to intervene but were driven back by the angry crowd. The 39th Regiment was called in, and a violent clash erupted at Parkhouse on Duke Street. The Riot Act was read (I'll write about this later), and musket fire killed three weavers and injured others. It was the first major industrial dispute in Scottish history, and those fallen weavers became Scotland’s earliest working-class martyrs.

The unrest didn’t end there. In 1800, food riots broke out in Calton. In 1816, a soup kitchen sparked another riot that had to be quelled by troops. By the 1830s, Calton’s handloom weavers were among the most impoverished of the skilled working class. Entire families—men, women, and children—worked the looms just to survive. During economic downturns, many had to pawn their clothes and bedding to avoid starvation. Powerloom factories loomed large as a threat, and in 1816, two thousand rioters tried to destroy such factories in Calton, even stoning the workers.

Wages plummeted. An 1812 inquiry revealed that regulations from 1792 were no longer being followed. Pay had dropped from 18 shillings for six days of work to just 8 shillings. By 1834, another inquiry found that while employment was high, poverty was rampant. The average workweek was 13 hours a day for six days, earning just over 6 shillings—minus rent for the loom frame.

Women had long been part of the weaving workforce, but male weavers saw them as competition. In 1810, the Calton association of weavers tried to restrict female apprenticeships to weavers’ own families. In 1833, male cotton spinners violently protested against female spinners at Dennistoun’s mill.

Children weren’t spared either. In New Lanark, one factory owner found 500 children working there, most between five and eight years old, taken from poorhouses. Though they were fed and clothed, many showed signs of stunted growth.

Another mill owner argued that depriving these children of work would cause hardship for their families. A 1833 Factories Inquiry Commission found that children were often too tired to eat and couldn’t dress themselves in the morning. Scotland was singled out as particularly harsh, with fatigue leading to serious accidents.

By the 1840s, the weavers’ once-proud reputation was fading. Poverty kept many from attending church or educating their children, and their moral and intellectual standards were said to be deteriorating. A magistrate’s report to the British Association described widespread pilfering, including the “bowl weft” system, where weavers and winders embezzled yarn and sold it to small manufacturers to supplement their meager wages.

Tragedy struck again in 1889 during the construction of Templeton’s Carpet Factory in Calton.

Designed to resemble the Doge’s Palace in Venice, the building was a marvel—but on November 1, part of a wall collapsed, trapping over 100 women working in the weaving sheds behind it. Twenty-nine were killed, a grim reminder of the dangers faced by workers in the textile industry.

After Calton was officially incorporated into Glasgow in 1846, its story became part of the city’s broader industrial narrative. Glasgow expanded rapidly, and its textile mills, clothing factories, and dyeworks grew alongside carpet-making and leather industries. The deepened River Clyde allowed for better shipping routes, and the city diversified into heavy industries like shipbuilding and locomotive construction, fueled by nearby coal and iron supplies.

Faced with poverty and dwindling opportunities, many Calton weavers looked abroad. Emigration societies sprang up, and the British government offered assistance to settle loyal Scots in Upper Canada’s Rideau Valley. Between 1820 and 1821, nearly 3,000 people emigrated, founding the Lanark Settlements in what is now Lanark County, Ontario. Scottish place names like Perth, Glengarry, Lanark, and Renfrew still dot the region. Many of these settlers found work in newly opened woolen mills, continuing the trade they had practiced back home.

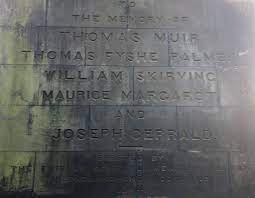

Since then modern Glaswegians have honored the Calton weavers with memorials at the Calton Burial Ground in the Abercromby Street Cemetery in Glasgow.

The legacy of the Calton weavers is woven into the fabric of Scottish history. From their rise as respected craftsmen to their struggles during industrialization, their story is one of perseverance, community, and the fight for dignity in the face of change. Whether in the streets of Glasgow or the mills of Ontario, their threads stretch far and wide, reminding us of the human cost behind every piece of cloth.

_edited.jpg)